The latest series of ‘The Apprentice’ just came to an end in the UK and, if you were among those following, you’ll know the winner was a man called Mark Wright, who gained a £250,000 investment (roughly $400k for any Americans reading), to spend launching a Digital Marketing Agency.

Not an original idea, but sensible nonetheless:

- Digital marketing has grown hugely over the last 15 years, and is still very much on the up.

- Mark – the winner – worked for a digital marketing agency for 18 months, and thus he should have some knowledge of the industry (or, at the very least, know how selling services works within a certain segment of the industry).

- Finally, Alan Sugar is a big brand capable of reaching the small businesses to whom Mark is planning to sell his services.

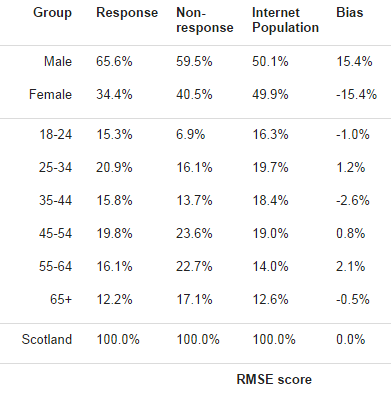

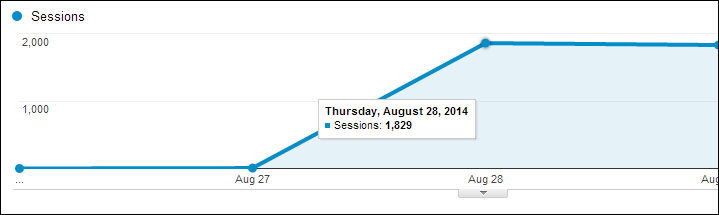

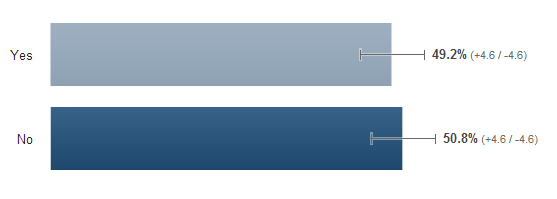

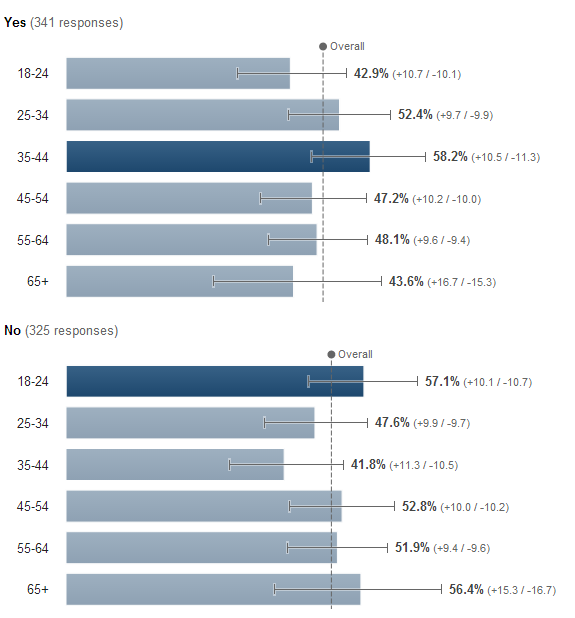

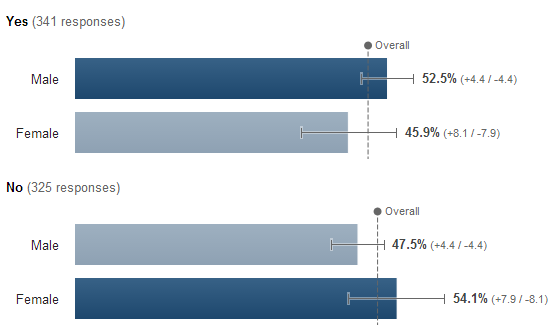

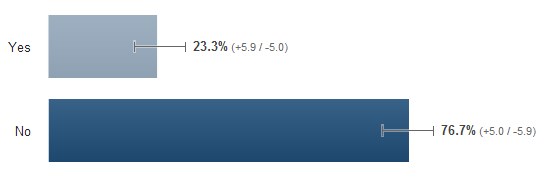

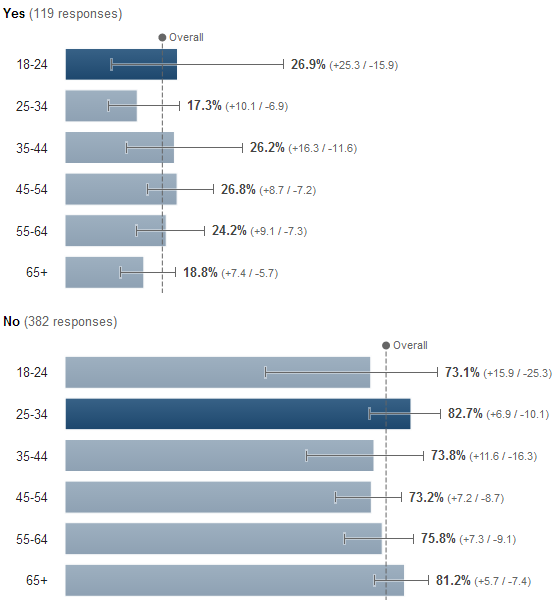

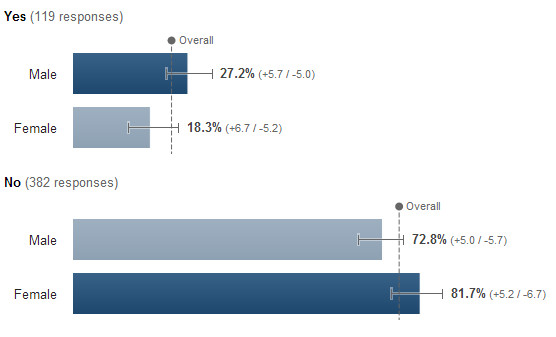

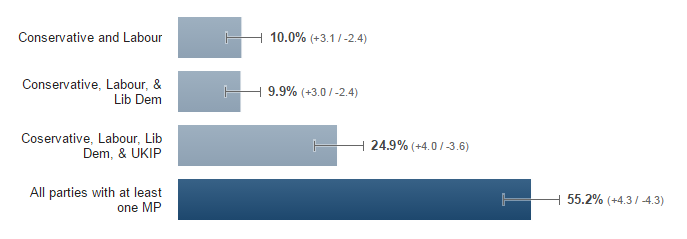

Surprising therefore that shortly after the show I conducted a straw poll of digital marketers asking if the £250,0000 went to the right person. After 40 minutes, the response looked like this:

Here are results so far from Digital Marketers re: “Do you think @Lord_Sugar should have invested in ‘Climb Online’?” pic.twitter.com/eo7LuuTTo2

— dan barker (@danbarker) December 21, 2014

The show was very entertaining, and there were plenty of positives about it, but one of the most notable elements was the number of basic Digital Marketing errors they made. Here is a selection of 5 glaring errors that may help answer why so many felt Alan Sugar may have made the wrong call.

(For fairness purposes, it’s worth disclosing that I’ve worked in digital marketing for 15 years or so, have worked with probably a few dozen digital agencies across that period, and know a couple of people who appeared on the show)

Error 1. No Available Domain Name.

The winning business idea was a Digital Marketing Agency called “Climb Online“. It’s not always a deal breaker if you miss out on the ideal domain name, but it certainly helps. Sadly, neither ‘ClimbOnline.com’ or ‘ClimbOnline.co.uk’ are available: they’re both already owned by rock climbing sites. The rules of The Apprentice meant they weren’t allowed to research this while the episode was being recorded, so you may say it’s excusable to have picked a company name without securing the domain. But, of course, Mark should have had this idea in his head for the entire series, and could have therefore done a few minutes research beforehand and bought a couple of relevant domains.

(Incidentally, the business Mark previously worked for was ‘Reach Local’; ‘Climb’ and ‘Reach’ are vaguely similar, and the business was of course also a Digital Marketing Agency offering similar services to his idea. On the one hand that means it’s a proven idea; on the other hand it doesn’t sound particularly original).

Error 2. Giving Away The Winner.

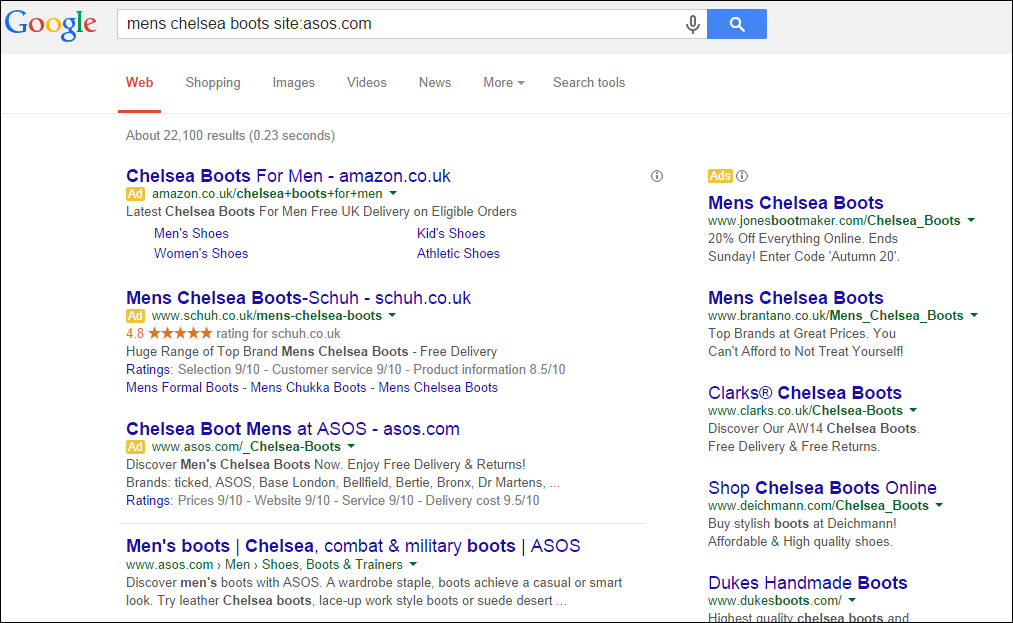

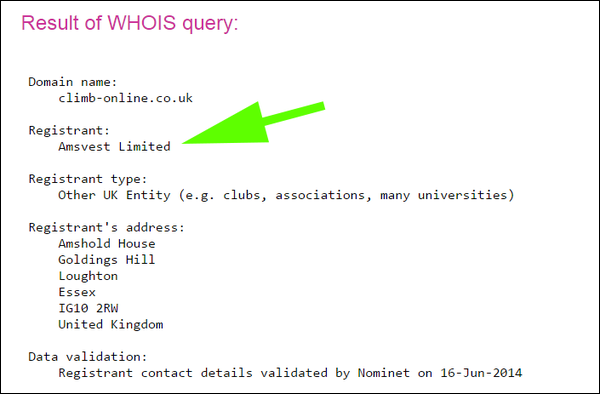

While ‘climbonline.co.uk’ and ‘climbonline.com’ were gone, it seems The Apprentice team did manage to register ‘climb-online.co.uk’ (and .com). In doing so, they also gave the game away somewhat for anyone savvy enough to check. Alan Sugar is of course ‘Alan Michael Sugar’. He owns various companies: Amstrad, Amsprop, Amstar, Amstique, etc. It does not therefore take a genius to spot it’s him that’s purchased ‘climb-online.co.uk’:

If they’d wanted, they could have registered a couple of ‘red herring’ domains for the other contestant, but sadly they did not appear to have done that. This basically meant quite a few people figured out the winner early on into the episode. As a side-note along with this, hyphenated domain names are generally seen as harder to make work than those without hyphens (they tend to sell for roughly 1/10th the cost of those without hyphens).

Error 3. Missed Opportunities.

The Apprentice is one of the most watched shows on TV. The final itself generates millions of views, and reams of other coverage on TV news, newspapers, etc. If you were in the process of launching a Digital Marketing Agency, you’d think you may want to capitalise on that absolutely enormous opportunity. Let’s do a little maths:

- A figure of £3,000 a month was mentioned for ‘Climb Online’s services. (or £36,000 a year)

- The opening episode of The Apprentice got 6.6 million viewers this year.

- The investment amount was £250,000.

- £36,000 x 7 = £252,000.

Therefore, Mark needed only to create 7 customers who would last a year to cover the investment amount (of course this excludes costs, etc, but a rough target to aim for). That’s roughly 0.0001% of the viewers of the show. Surely a quick website with a big “Interested in our Digital Marketing Services?” email address form could manage that…

In reality very little happened.

Alan Sugar gave his usual commentary throughout the show on Twitter, and in doing so managed to get 50,000 extra followers for Mark (who only very recently joined twitter). A few of the more basic missed opportunities included:

- Neither Mark nor Lord Sugar mentioned the company website at any point.

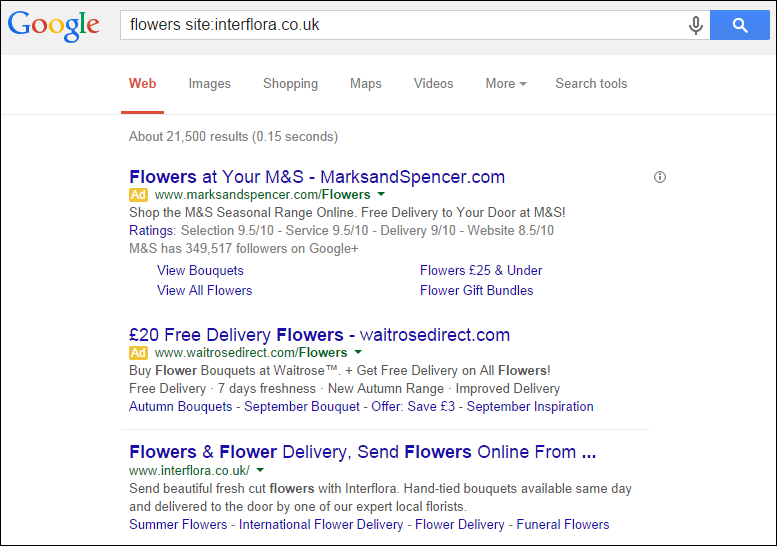

- A Google search for the company name didn’t yield any results related to their company.

- There’s no link in Mark’s twitter bio to the company.

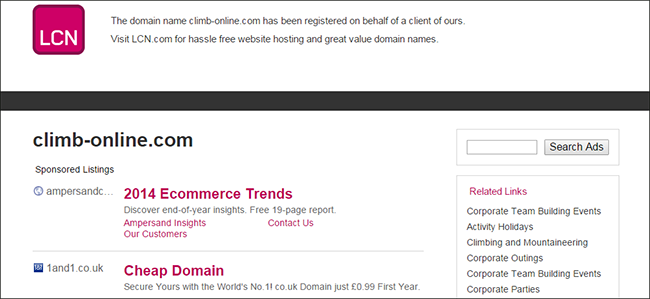

Despite registering those domain names months ago, there was no website available at the end of the show. And, the day after the show, as all of the press stories land, the domain names still look like this:

(for anyone unaware, that’s the standard page that goes live when the domain was purchased).

In other words, millions of people watched a TV show that told them “hey, this guy is offering Digital Marketing Services”, but if you took a look online – the realm of digital marketing – you’d find nothing at all to back any of this up. As a reminder: the winner, Mark, previously worked for a Digital Marketing agency that specialised in lead generation – you would expect him to have set up at least some sort of method of gathering leads for his new business. Ironically, the ‘loser’ did a slightly better job: she at least set up a twitter account for her company (even if the website was still ‘coming soon’).

(update: a few people have mentioned the BBC’s guidelines around promotion. I don’t think that would have precluded them from launching a website, but do feel free to read here & let me know what you think: http://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/page/guidance-conflicts-advertising)

Error 4. Company Name Clarity

The company name used in the show was “Climb Online”. Millions of members of the British public are now (at least vaguely) aware of that name. It’s the kind of exposure you literally cannot buy (despite the domain name blunder), and Mark is still tweeting referring to it by that name (even if he doesn’t quite know how to share an image in the correct orientation):

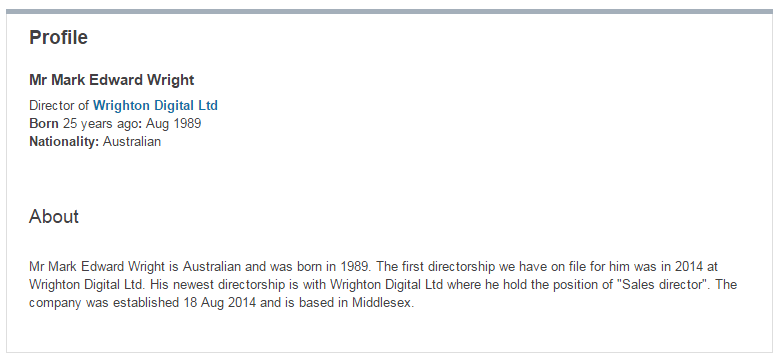

Despite all of that, he seems to have registered – and be trading under – a different business name (“Wrighton Digital Ltd”). Here’s his directorship record from DueDil:

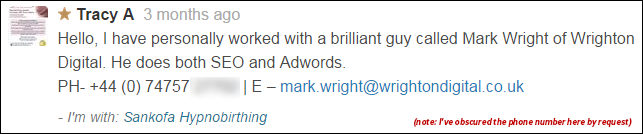

Note the company name there, ‘Wrighton Digital Ltd’. Alongside that, a couple of people who apparently either know Mark, or were involved with the show have mentioned this is his new brand:

If you hunt around, there are various other references to this. There’s an ‘Avon Coaches’ website that claims to be ‘Powered by Wrighton Digital’, and a few forums reference the business:

Of course, that may simply have been a temporary cover story to avoid the result leaking to the press, but a simple announcement would clear it all up & generate a ton of press, links, etc for the real business. There are 3 possible alternatives there:

- It’s a cover story, and the business will be called Climb Online. In which case it’s madness that they didn’t have the site ready to go at the end of the show at ‘climb-online.com’ or .co.uk.

- They have gone for a rebrand, and it will no longer be called Climb Online. In which case it’s madness that they didn’t mention this at the end of the show, or at least announce it on twitter & run some Google ads against the phrase ‘climb online’ to communicate the new name to anyone who searched for the name.

- This is something Mark’s running by himself, under the radar. Unlikely I think.

Whichever the answer, it would be very easy to have fixed this.

Error 5. Nabbed Twitter Account.

The next clanger here is on a level similar to some of the above: a fairly fundamental error that would have been easy to avoid with a bit of foresight.

- twitter.com/climbonline is, of course, already taken (and they say they’re not going to hand it over)

- twitter.com/climb_online was registered by someone after the final.

- twitter.com/wrightondigital was registered by someone after the final.

Neither of the newly registered accounts appear to be owned by Mark Wright, or Alan Sugar. It would have been simple to register either/both for anyone who knew the business name beforehand (ie. Mark or Alan!)

Summary

Of course, it’s a TV show & meant for entertainment rather than to display ‘best practice’. There were probably lots of restrictions on what could/could not be done for the purpose of keeping the winner secret. And, of course, there are always going to be errors in something like this & that’s fine, but the errors pointed out here are fairly basic. There were dozens more errors & omissions surrounding this, but those are barely worth mentioning alongside the above.

All of this is a shame from 2 points of view:

- It’s great when Digital Marketing makes it into the mainstream. It would be even better if this were represented in a 100% positive light, which these basic errors do not assist.

- If Mark had got things right, he could quite easily have gathered enough interest to cover the £250,000 investment immediately. Instead, it seems he’ll go down the old school sales route (he came across as an extremely able salesperson). That’s completely fine, but it’s very sad that a digital marketing business would fail to cover the digital marketing basics above.

Ironically, in the post-show interviews, Alan Sugar said one of the reasons he chose to hire the winner was that Google UK’s MD had advised him to do so. It seems he wasn’t aware that the person he was talking about had left Google in the intervening period.

Very good luck to them both, and I hope the show has inspired many more people into digital marketing. Do leave any comments below, or share this post with others if you think they’d find it useful.

ps. I send out emails occasionally with content like this. Feel free to sign up if you’d like.

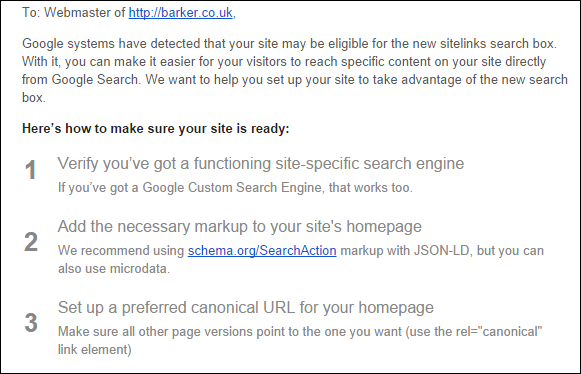

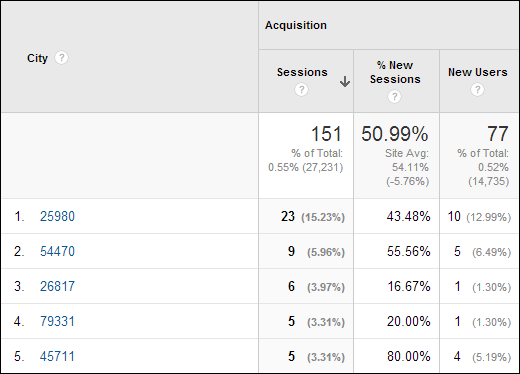

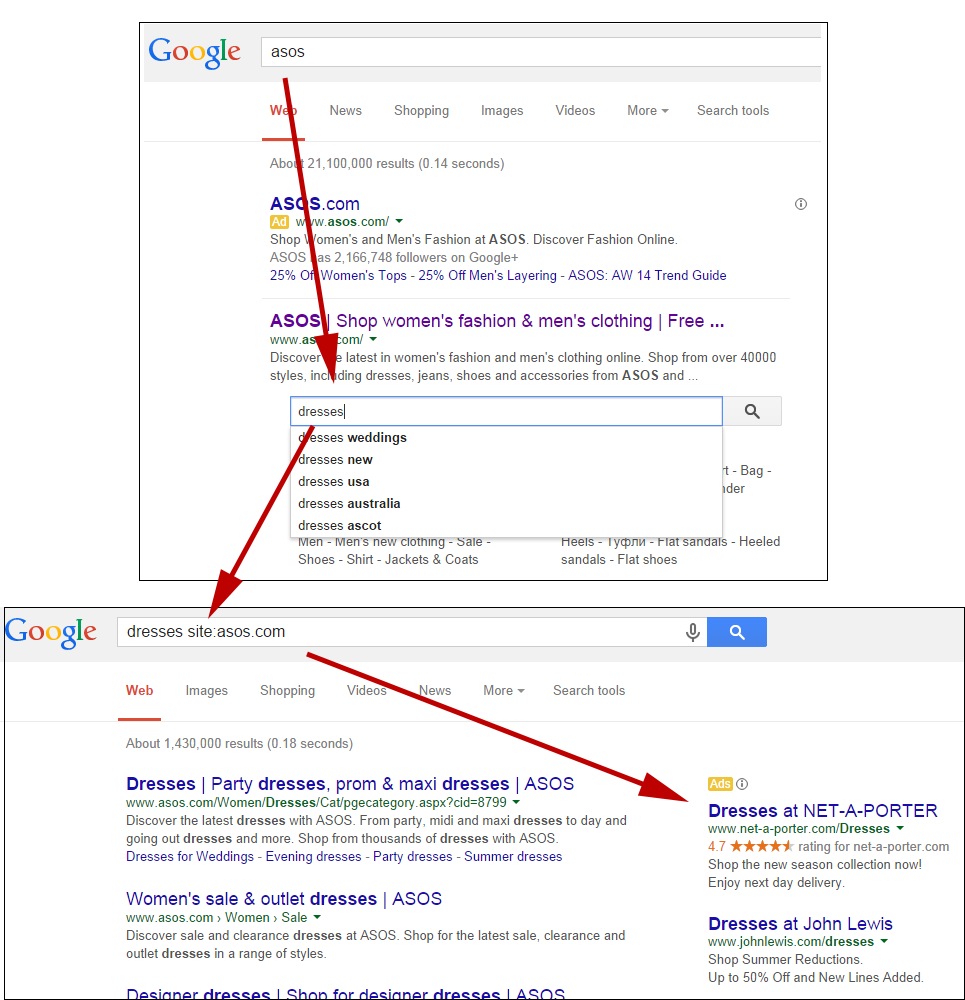

Here’s the user journey there, in case you find that difficult to follow:

Here’s the user journey there, in case you find that difficult to follow: