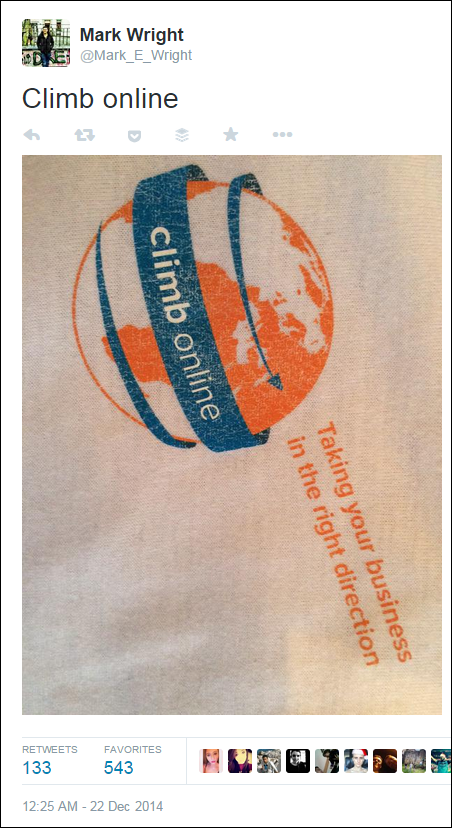

Here’s a tweet that sums up the depressing state of the London property market. You may well have seen this:

Only… if you spend 2 minutes looking into it, it may not be all it seems.

As you can see, it was retweeted well over 4,000 times (probably many more if you take into account quote retweets, that don’t show up in the number). It was also picked up by various news outlets, including the BBC, the Mirror, Sky News, the Metro, the Telegraph and many, many more:

Looking into it further, the first 4 oddities are:

- The tweeter started directing the ‘story’ to various newspaper twitter accounts, very shortly after sharing it.

- The twitter account had been fairly inactive for a while up until this point, and then suddenly seemed very active.

- If you look closely at the photos – something is quite odd. The ‘bed’ doesn’t actually seem to be a bed – it’s just a folded up duvet on the floor. The pillow has no pillowcase. The items in the room are the sort of items you’d find in a utility room, or a cloakroom. In other words, it doesn’t actually look like the room is used as a bedroom – just like it’s been hastily mocked up to look like a room containing a bed.

- Pretty much every news article mentions (and links to) a particular website “London2Let”, where the tweeter says she found the room. That’s a detail, but quite surprising that almost every article contains it.

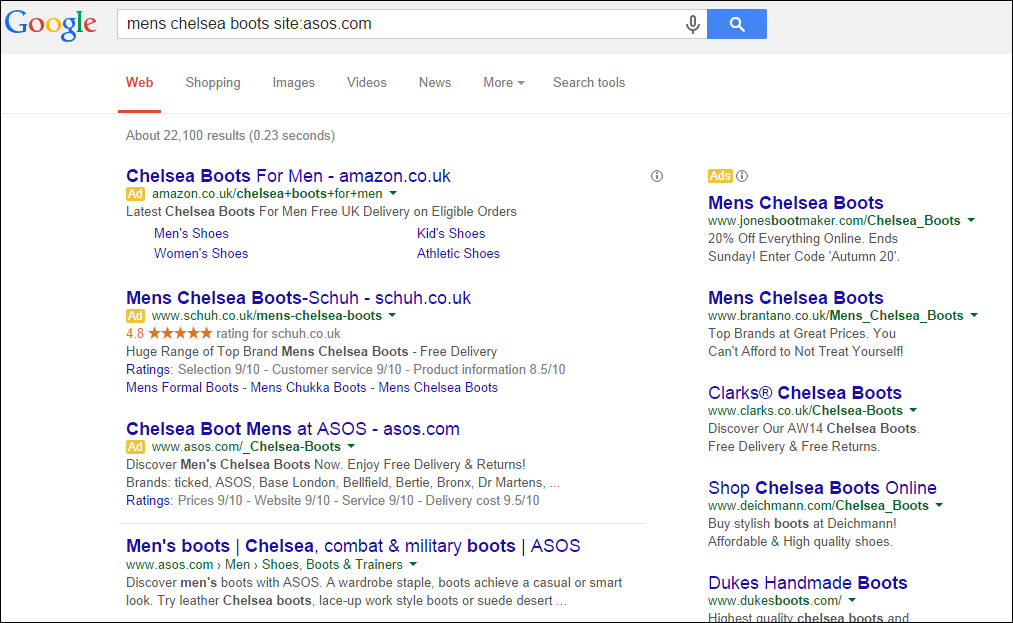

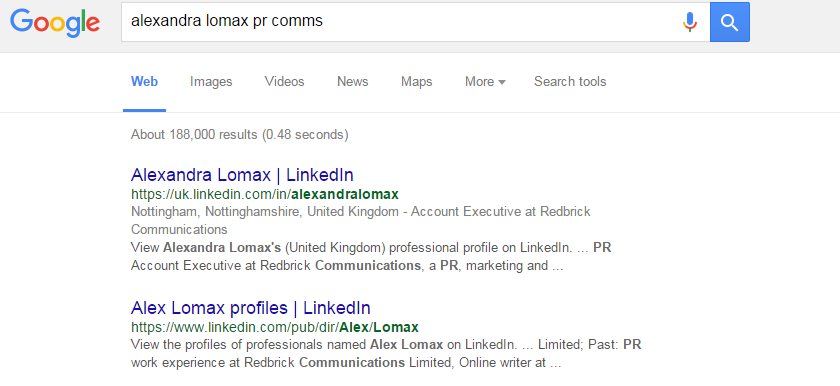

And following on from that with a couple of quick Google searches, it continues to look odd. A google search for ‘alex lomax’ doesn’t show up very much, but one for ‘alexandra lomax’ along with PR-related terms shows up this:

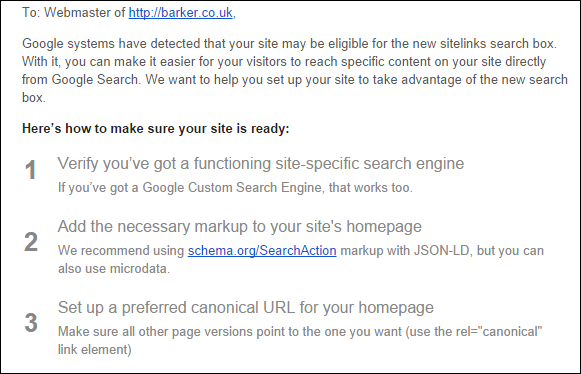

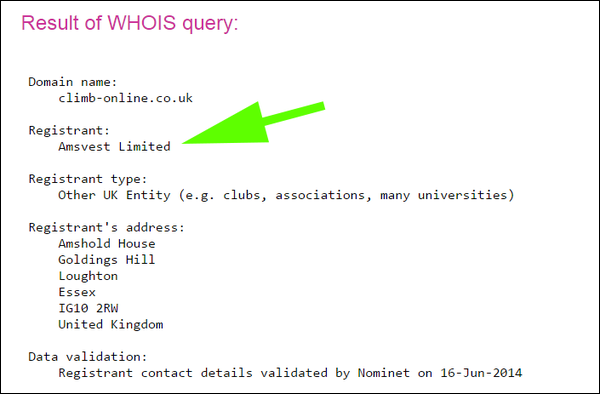

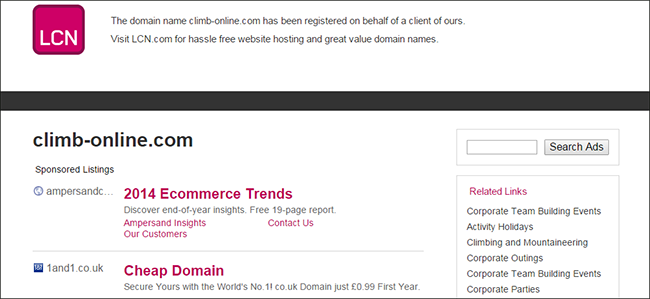

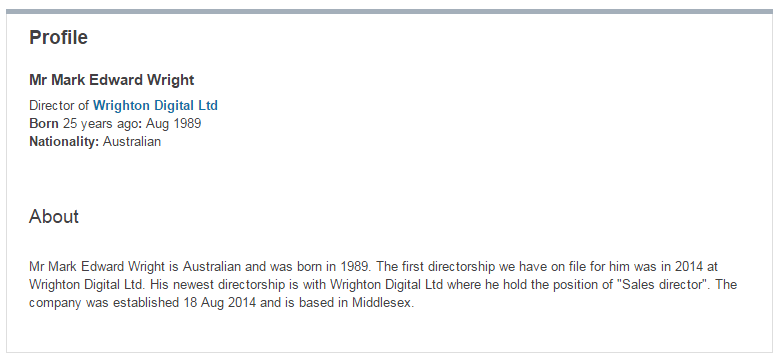

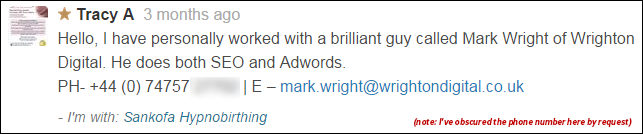

‘Redbrick Communications’ – the employer mentioned there – is a PR firm, whose website says one of their specialist areas is the housing market. That perhaps may trigger a little alarm: PR firms essentially specialise in getting the messages of their clients out to the general public. Often they do that specifically by trying to ‘place’ stories in the media. Sometimes those stories are judged on column inches (whether the client’s name is mentioned in articles), sometimes over recent years they have begun also to be judged on links (a link from a high quality site is worth a little from the point of view of the visits it will bring directly; a link is also more highly valued on the basis that it may cause Google to rank a particular site higher in the search rankings for a given relevant term). So at some stage, the tweeter worked for a PR firm.

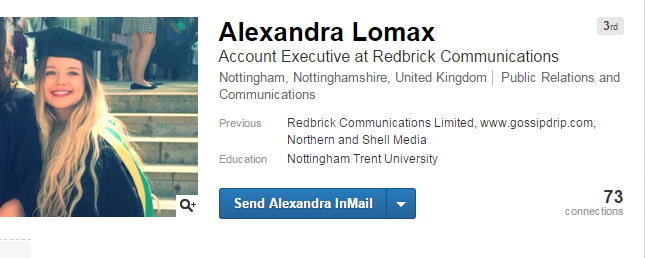

If you clicked through the LinkedIn link earlier in the day, you’d find a picture of Alexandra that matched the one in @alex_lomax’s Twitter profile:

If you clicked through a little later in the day, you’d find the profile had suddenly been limited, resulting in this:

That rings another odd alarm bell. Why would someone suddenly set their LinkedIn profile private, while simultaneously soliciting newspapers to cover a story from their Twitter account?

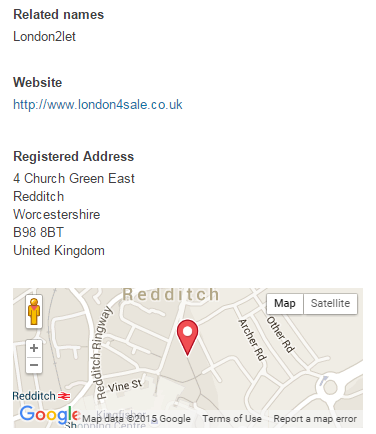

And 2 or 3 further Google searches show that Alex is from Worcestershire where, coincidentally, London2Let’s office address is based (as mentioned by Luke):

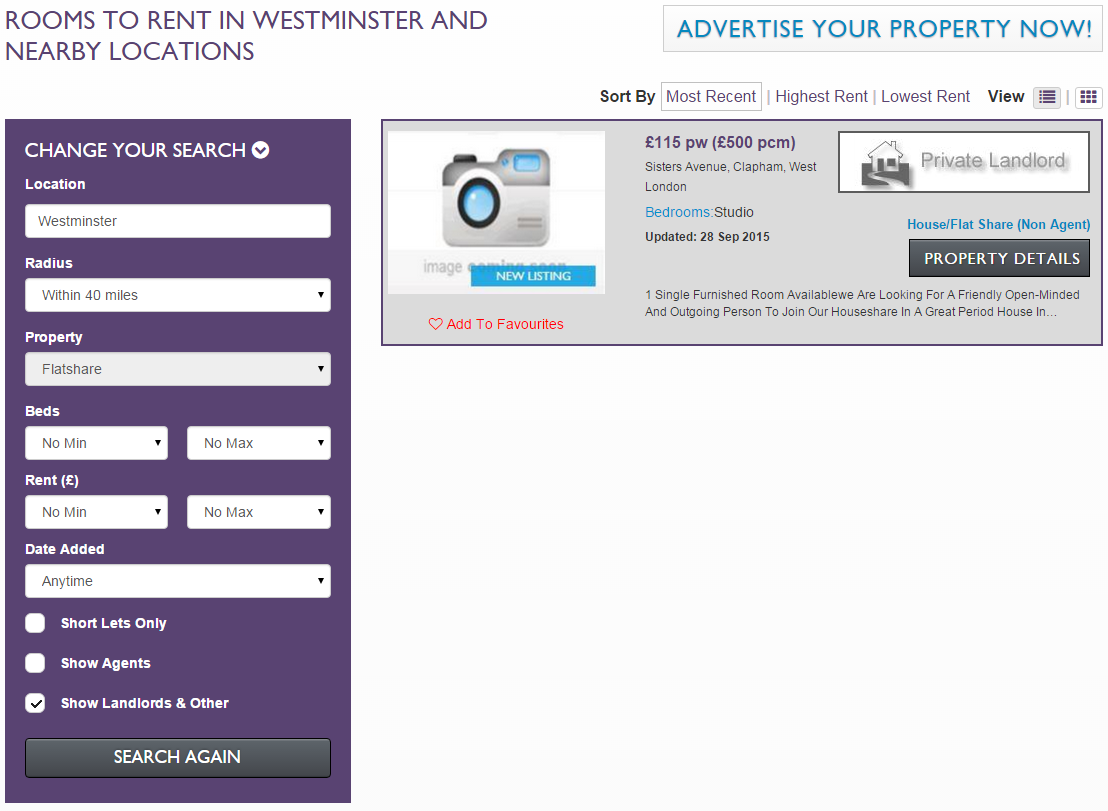

Look further still and it continues to look odd. Here’s the ad for the room:

There are a couple of odd things about that:

- The wording of the ad. “not really looking for somebody that just wants to stay in their room” sounds like a joke when you think back to the original ad.

- The “room comes with a bed” point.

The second point isn’t perhaps immediately obvious, until you remember that the photo of the room didn’t actually contain a bed – just a duvet folded up on the floor:

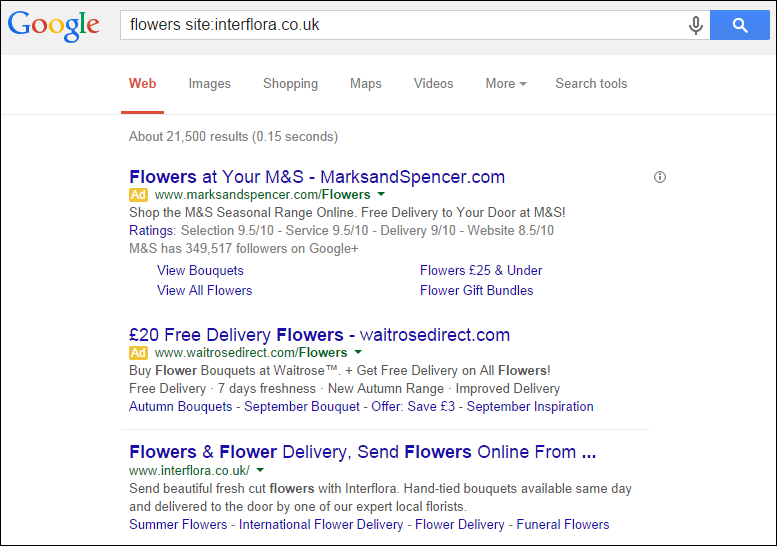

Look a little further still into the ad and you find this oddity:

Within 40 miles of Westminster, there is only one ad on the entire site from a private landlord. That ad is the one in question. In other words, across the whole of London, there is a single private landlord ad on the site, and that ad happens to be the one that’s gone viral. (note added after a question from Jim Waterson: If you’d like to verify this, go to the London2Let site, search for any london location, set the area as ‘within 40 miles’, choose ‘flatshares’, and untick the option to show ads from agents – ie. private landlords only).

Conclusion

So is the ad real? The answer is I don’t know. Alex didn’t answer when I asked questions about it. I tried to call the advertiser, but they weren’t accepting calls. Some possibil犀利士

ities are:

- Maybe they’re a hoax advertiser.

- Maybe Alex is doing PR work on behalf of a company

- Maybe she’s helping out a friend with a bit of work to help boost their lettings site.

- Or quite possibly it is real, and I am overly cynical.

The story feels suspicious to me, and there are lots of little red flags if you spend all of 2 minutes digging into it. Lots of the UK’s biggest news outlets seem to have published it without doing those 2 minutes of due diligence. In terms of website traffic, it’s often more important to be quick to publish a developing story than to be thorough. If the story is real, I’ll happily pay Alex’s first week of rent for doubting the story whenever she does find a suitable place (hopefully with a little more space, and an actual bed rather than a folded up duvet on the floor), but the story doesn’t quite add up to me as it has been presented.

Whatever the answer, well done to her on the viral story.

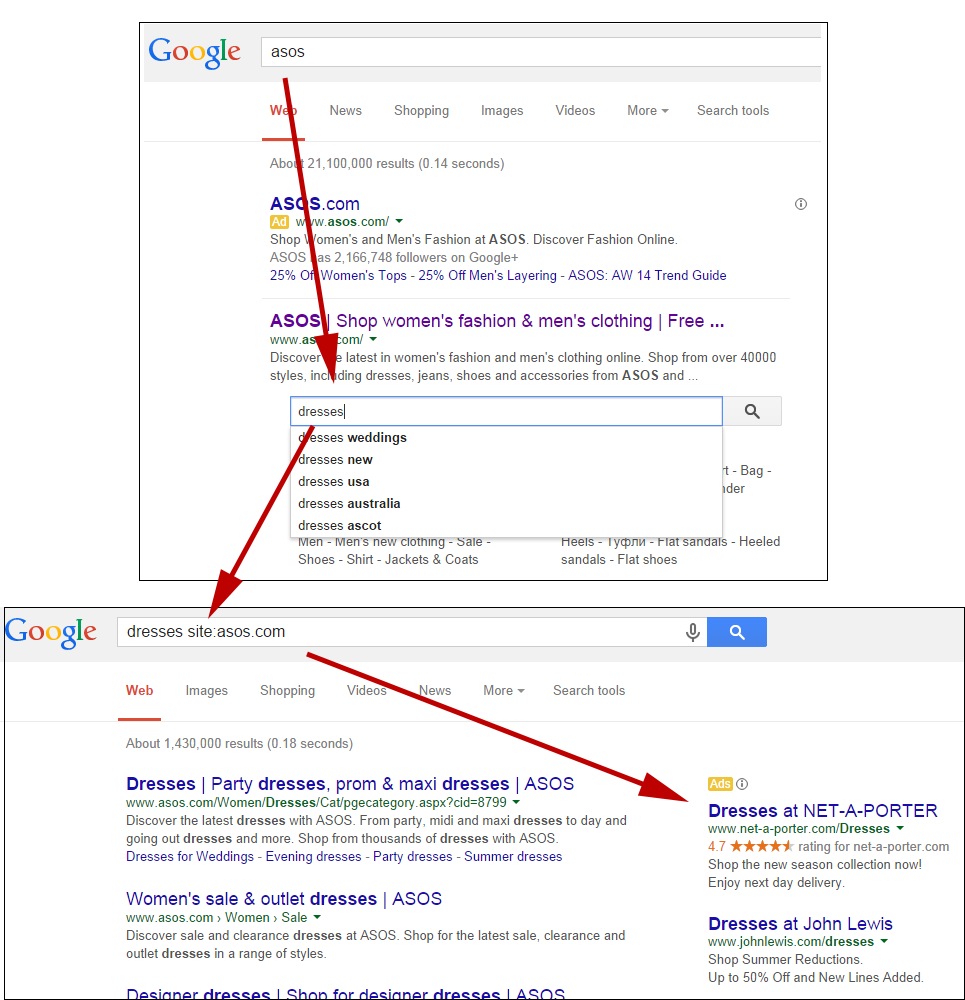

Here’s the user journey there, in case you find that difficult to follow:

Here’s the user journey there, in case you find that difficult to follow: