Twitter and Google regularly do something that – if you or I did it – would be breaking the law. They reveal the identities of people who courts have decided should not be named. If newspapers and members of the general public name them, there are very serious repercussions. Yet Google & Twitter’s algorithms seem free to do this.

Today they are doing it again, in relation to the killers of a 39 year old woman.

One of the saddest legal cases you may ever read is that of Angela Wrightson. She was killed by two teenagers – 13 and 14 at the time – who inflicted more than 100 injuries on her. Today a judge sentenced them both to life in prison, serving a minimum of 15 years. The full, shocking, detail is here: https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/sentence_F_D.pdf

In considering whether Angela’s killers should remain anonymous, or whether newspapers, news media, and the general public should be allowed to reveal their identities, the judge said many things, including that it is likely to pose a great danger to them:

The judges summary was this:

I suspect some of us would agree with the above, and some would argue that they are murderers, and have brought it upon themselves. Either way, however strong they are, your feelings & my feelings are irrelevant: a judge has decided that there is a ‘real and present danger’ to these two girls, references suicide attempts, and therefore summarises that they must remain anonymous.

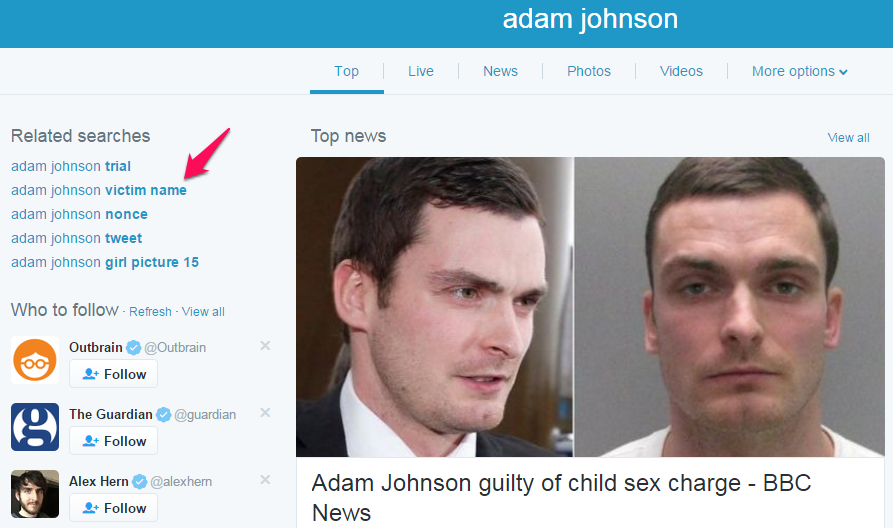

Yet, clicking on the victim’s name on Twitter, which has trended for much of the day, reveals 2 girls’ names:

Angela’s name trended across the UK. In other words, if you have used Twitter today, you were a single click away from seeing the names of two people who a judge had deemed should not be named.

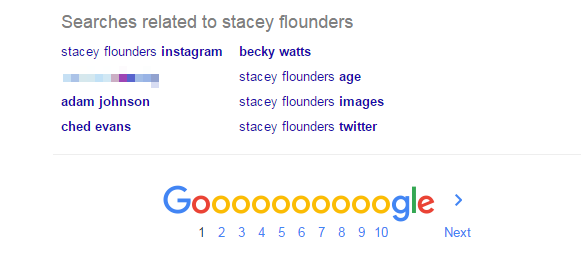

And, as I have written about before, Google does a very similar thing, at the foot of search results:

This happens automatically, because both Google & Twitter have algorithms that associate related searches to each other. In other words, the algorithms are breaking the law.

I have written about this several times over the last few years:

- Twitter & Google both showed photographs of one of James Bulger’s killers, when searching for broadly related terms: http://barker.co.uk/algolaw

- The footballer Adam Johnson’s 15 year old victim was named http://barker.co.uk/algorithmlaw

- In recent days, a very high profile celebrity was named by Twitter’s algorithm, when searching for the initials he had been given by the UK courts to conceal his identity.

- And, again, it is happening today.

It is not right that this should happen. It is dangerous both in cases like this – for the killers, for their friends, and those associated with them – and it is most definitely not right in examples where victims are named.